Re-hydrating at Kenosha's Rendez'vous tiki lounge

By John Greenfield

I’ve cycled from Chicago to Milwaukee, mostly on highways, a dozen or more times. But recently I made the trip over two days using a route that is 80 percent off-street paths. I was encouraged to slow down and enjoy the ride by some laid-back, fun-loving dudes from New Belgium Brewing, makers of Fat Tire beer.

The guys were in town to stage the brewery’s Tour de Fat festival, a celebration of bicycles and beer that travels to a dozen or so bike-friendly cities. All the proceeds from beer and merch sales go to local cycling non-profits, in this case West Town Bikes / Ciclo Urbano, a community bike shop and education center in Humboldt Park, which received $20,000 this year.

Bike parade at the Tour de Fat

This year’s Chicago event in Palmer Square Park started with a raucous bicycle parade around the community. The carnival included performances by the local “circus punk marching band” Mucca Pazza and like-minded out-of-towners, a corral full of freak bikes to test ride, and the opportunity to trade your car for a shiny new Black Sheep bike, built in New Belgium’s hometown of Fort Collins, Colorado.

Mucca Pazza at the Tour de Fat

Michael, Brian and Andrew from New Belgium were interested in pedaling to Milwaukee, the next stop on the tour, and West Town’s Alex Wilson tapped me to serve as their Sacajewea, guiding them across the Cheddar Curtain. The guys wanted a leisurely, low-traffic ride broken up over two days, since none of them had much touring experience.

I decided we’d stick to the route outlined in Peter Blommer’s

Biking on Bike Trails between Chicago and Milwaukee (Blommer Books 2003). Since the route’s a bit longer than taking highways and much of it is on wheel-slowing, crushed limestone paths, I’d always been afraid it would be two much for a one-day ride, so I was psyched at the opportunity to finally test it.

I pick them up on Monday morning at their Mag Mile hotel. I’m mildly alarmed by their motley assortment of rides – an old road bike, a hybrid and a front-suspension mountain bike with 29” wheels – and the fact that two of them are hauling their gear in backpacks.

Also joining us is Chad, a young bike mechanic from Palatine who met the guys recently when he rode from southern Illinois to Fort Collins. In Kansas he had knee problems – his knees were swollen to the size of basketballs. Chad’s riding a bling-y turquoise-and-red Gunnar.

We head north on the Lakefront trail in the sunshine, pausing at the North Avenue chess pavilion to take the obligatory snapshot with the Hancock Tower in the background.

Chad, Michael, Brian and Andrew

After we leave the trail and get on the signed on-street route to Evanston, Michael says his bike’s crank is feeling funny, so we stop at Roberts Cycle, 7054 N. Clark for a check-up – all’s well. Continuing north on Clark we exchange greetings with an old lady with dreadlocks in a pink dress on a cute basket bike.

After entering Evanston, instead of staying on Sheridan Road we hug the lakefront, picking our through paths in the lakefront parks and connecting side streets to the small harbor by the Northwestern campus. We cross a bridge to a peninsula and take one last, breathtaking view of the Loop.

From there we stair-step northwest via Lincoln, Asbury, Isabella and Palmer to Poplar, which takes us to the southern terminus of the paved Green Bay Trail, which parallels the Metra line towards Kenosha, WI. Andrew caws like a crow as we ride through wooded areas in Winnetka. We encounter a teen dragging a bike without a front wheel – he says it’s been stolen.

After the trail ends in Highland Park we take streets up to Highwood, stopping to watch the World Cup at Bridie McKenna’s, a cozy Irish pub at 254 Green Bay. We soon pick up the Robert McClory Trail, which is paved until we reach the Great Lakes Naval Training Center. A cloverleaf takes us a bit west through North Chicago where the trail becomes crushed limestone through residential areas with frequent street crossings.

In blue-collar Waukegan we see old folks tending crops in community gardens that run parallel to the trail – a good use of the spare land. We stop for another brew at Booner’s Place, 1210 Washington St., a bare-bones dive adjacent to the trail.

We continue north on the trail, then take another break on a path-side knoll. The New Belgium guys are exhausted and saddle-sore. “There are more fit people who work at New Belgium,” apologizes Brian. “They’re not all this lame.”

We’ve been using the Chicagoland Bike Map so far. Crossing the border into Wisconsin on the Kenosha County Trail we switch to the excellent Milwaukee and Southeastern Wisconsin Bike Map, available in Chicago at Boulevard Bikes. Just before the trail ends we zigzag into downtown Kenosha, the state’s fourth-largest city, on 93rd and 91st Streets and 7th Avenue.

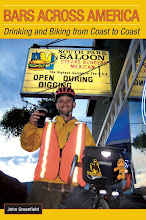

We’re spending the night in a harbor-side motel in Kenosha, and that night I achieve a long-time goal: drinking at the Rendez’vous Tiki Lounge, 1700 52nd St. I’ve heard about the place from James Teitelbaum’s book

Tiki Road Trip but never got to visit it on any of the occasions I passed through town because it doesn’t open until early evening.

The place doesn’t disappoint, with tasty Mai Tais and densely packed décor: classic faux-Polynesian mixed with pirate and punk rock elements. In addition to the usual grass mats, Easter Island heads, plastic sea creatures and ukuleles, there’s a large mural of a beach scene rendered in black and blood red, and skeletons and Jolly Roger flags abound.

The next morning the New Belgium guys are hurting from the miles. “I got a dino-sore in my pants,” says Brian. “A mega-sore-ass.” Andrew hires a cab to take him to Milwaukee with his bike, but the other guys decide to soldier on.

We head up a scenic lakeside path on the north side of town, then cut west to the northern section of the Kenosha County Trail. A woman is pedaling in the other direction towing a trailer with a dachshund and another mutt that looks like Benji.

Kenosha's lakeside bike path

Several miles later we enter Racine, the state’s 5th largest city, and pass by Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous Johnson Wax Building. Downtown we see a hundreds of people lined up outside the civic center. President Obama will be hosting a town hall meeting the next day and people have been lined up for tickets since 10:30 pm the previous night.

We take a break near the zoo on a cliff overlooking Lake Michigan. Nearby film crew shoots three cyclists in matching Lycra outfits for an episode of the local TV show “Discover Wisconsin.” A guys cruises by on the lakefront bike path on a giant ATB unicycle with knobby tires.

Heading west again, we pick up the north Racine Trail and take it for a half hour or so until it ends at Six Mile Road, six miles from downtown Racine. From there we get on Route 32 and enter the Milwaukee suburbs. At Ryan Road we head east and the north on 5th Avenue, quieter than the highway, which eventually takes us downhill to a pretty little waterfall.

We soon get on the Oak Leaf Trail, an undulating path through the forest along the lake south of Milwaukee, which eventually brings us into Milwaukee and affords a nice view of the city’s modest skyline. We meet up with Dave Schlabowske, the local bike coordinator, at the Palomino, 2491 S. Superior St., a southern-style restaurant and bar in the hip Bayview neighborhood on the south side of town.

Riding into Milwaukee on the Oak Leaf Trail

We take Kinnickinnic and 2nd St. downtown and I take the guys to their hotel, where their freaky, cowboy shirt-clad colleagues from New Belgium greet them. Later that afternoon the brewery hosts a reception for local beer distributors at Café Centraal, 2306 S. Kinnickinnic, a Belgian-style tavern. There I get to meet co-founder Kim Jordan, and thank her for the company’s $20,000 donation to West Town Bikes.

Chad with a New Belgian at Cafe Centraal

Afterwards the guys head to the Summerfest music festival on the lakefront. Before I join them I drop into the downtown Amtrak station to buy a bike box for my ride home to Chicago that evening, since I need to work the next day. I’m taking a midnight Megabus, since I’ve missed Amtrak’s last run for the day.

But when the Amtrak baggage agent hears I want the box in order to bring my bike on Megabus, whose cheap service to Chicago has cut into the rail company’s business, he refuses to sell me a box. I go back and forth with him for a while on this, then sneakily ask him to sell me a ticket for the morning train plus the box. “I’m not going to do that,” he says. “You’re just going to cancel your reservation and then ride the bus tonight anyway.”

I’m stymied. I can’t think of any way to convince this guy. Then it occurs to me to try anger. Fake anger, that is – while I often get annoyed, I almost never lose my temper. “This is very frustrating,” I say, banging my hand on the counter. “I’m a loyal Amtrak customer. If you guys had a late train I would take it. I just want to catch a little of Summerfest and go home, but because you’re being unreasonable I’m going to have to find somewhere to sleep here and then be late for work.”

“I spend a lot of money on Amtrak,” I say. “In fact, I’m taking the train again to La Crosse soon.” This does the trick. After he looks up my confirmation number for my next train-and-bike excursion, the Bars Across Wisconsin ride from the Mississippi back to Chicago, he sheepishly agrees to sell me a box.

I fold up the box and tie it to the back of my bike and then meet up with the New Belgium guys at Summerfest. A local beer distributor has gotten us VIP passes to, ironically, the Miller Beer Oasis. This gets us into a loft right above the stage for a set by Sound Tribe Sector Nine, a young band that plays techno-style music with live instruments. It’s exciting to be above the swarm of a thousand or two glow-stick toting fans, watching the octopus-armed drummer play hyperactive beats.

Sound Tribe Sector Nine

It’s time for me to head over to the Megabus stop, so the disarmingly touchy-feely New Belgium dudes thank me for getting them safely to Milwaukee and hug me goodbye. I pick up my ride from the attended bicycle parking lot and head a mile or two over to the bus stop. I tape the box together, take off my pedals and turn the handlebars and seal the bike inside.

Ironically, when Megabus shows up, the driver tells me he can’t fit my boxed bike in the cargo hold. I have to do some more negotiating, but finally convince him to throw my de-boxed bike on top of the other luggage. I fold up the box for my next bike adventure and climb aboard.